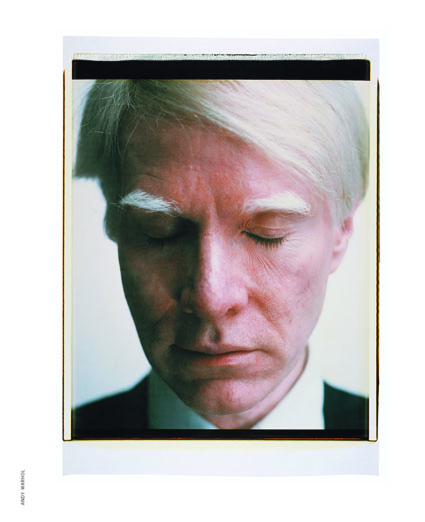

From Rembrandt’s over one hundred self-portraits to today’s selfies, from Warhol’s wigs to Snapchat filters: when depicting our faces is an art or just another way of wearing a mask

- Andy Warhol, “Untitled”, 1979, from “The Polaid Book”, Taschen, © 2004 Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / ARS, New York.

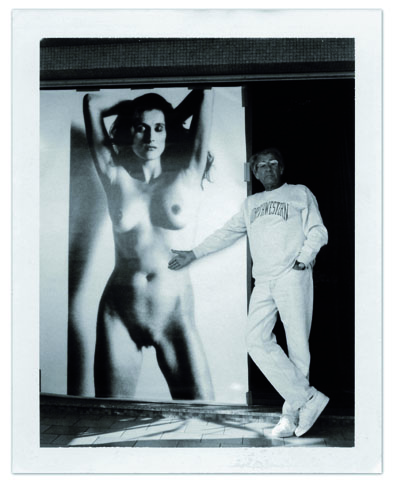

- Dennis Hopper, “Self-portrait at porn stand”, 1962, from “Dennis Hopper: Photographs 1961-1967”, Taschen © 2011 The Dennis Hopper Trust.

Taking a selfie four hundred years ago, from Rembrandt to the present day, the artist’s mania for self-portraits is now quite dated. As a sub genre of art it has been part of our artistic, cultural and social heritage for quite a time. Before the era of social networks there were once great noblemen’s houses, churches, museums and private collections to show off and boast about to your friends.

Every work of art speaks about its author and yet there is something more in the self-portrait: the face. Already common practice from the Middle Ages onwards and well established by the Renaissance, the reproduction of one’s own image raises a number of questions. However never trust the artist: between true-to-life paintings and pleasing pretences, light-hearted jokes and tricks of perspective, emotional parables and overdoses of Photoshop, history – and art itself – teaches us that life imitates Art a lot more than Art imitates life.

Reflections on the subject’s place in society, his political battles, his chosen and hidden affinities, snap shots and narcissism: here for you are the faces (only some of them) of those who have given us them, only to return to the fact that centuries pass but we, perhaps, remain the same.

CHAPTER I – I CAN SEE YOU

- Jan van Eyck, “The Arnolfini Portrait”, 1434, National Gallery, London

- Jan van Eyck, “Portrait of a Man (Self Portrait?)”, 1433, National Gallery, London.

It was 1434 when the Flemish painter Jan van Eyck painted Arnolfini and his wife in the intimacy of their own home. The couple are depicted at the moment of their marriage, hand in hand in the presence of two witnesses: van Eyck even painted himself and his assistant reflected in the mirror behind them. Apart from the play of perspective -the mirror shows who is doing the painting – which reveals a certain awareness of his own technical abilities, the presence of the artist in the painting signifies another concept of fundamental importance: the recognition of his own importance, his role in society, his status and not only as a witness to the union but also and above all as the author of the work.

- Raffaello Sanzio, “Autoritratto”, 1504-06, Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze.

- Raffaello, “The School of Athens”, 1509-1511 ca., Musei Vaticani, Roma.

Italians are masters of the hidden self-portrait: the first was Giotto who, in 1306, painted himself among the blessed in his Last Judgement in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, then Botticelli followed in the Adoration of the Magi (1475, the Uffizi) and a “camouflaged” Andrea Mantegna appears in grisaille among the decorative foliage on a pillar in the Bridal Chamber of the Castello di San Giorgio in Mantua (1465-1474). Raffaello, celebrating his role as artist, painted himself among a group of intellectuals and philosophers in his The School of Athens (1509-1511) with his gaze turned in complicity towards the observer

CHAPTER II – ALL KINDS OF FILTERS

It really doesn’t matter whether it’s an emotional filter, using colour and brush strokes, a disguise, a pose or a post-production effect, a self-portrait – even a selfie – is always an artifice: what I see is something someone has chosen for me to see.

Vincent van Gogh painted many portraits of himself over his lifetime, 37 of them between 1886 and 1889. For him art – and more particularly the choice of oneself as subject – was a way, perhaps the only way, of scrutinising his interior state of mind. He wrote to his brother about his Self-portrait of 1889: “You will notice that the expression on my face is much calmer, even though I think I look more unstable than before”.

- Andy Warhol, from “Myths”, 1981, from “Andy Warhol. Polaroids”, Taschen, ©The Andy Warhol Houndation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

- June Newton, “Self-portrait”, Ramatuelle, from “Mrs. Newton” Taschen.

- Ines van Lamsweerde, Vinoodh Matadin, “Me Kissing Vinoodh (Eternally)”, 2010, from “Inez van Lamsweerde/ Vinoodh Matadin. Pretty Much Everything”, Taschen, © Inez van Lamsweerde & Vinoodh Matadin/Taschen

- Helmut Newton, from “Helmut Newton. Polaroids, Taschen.

Years later Andy Warhol chose a completely opposite approach: eliminate the ugly, disguise yourself, use yourself only in the way you look your best, as an icon, a superstar, and American legend like Uncle Sam or Mickey Mouse. Yet even in his paintings the Faustian words “Stay, you are so beautiful” appear, leaving the observer with the sensation that the filter he chose is a superficial cover up for a great fear of living, together with a terror of dying. Certainly Warhol found the way in the end, because legend and art are eternal.

CHAPTER III – L’ARTISTE C’EST MOI

Why paint a portrait of yourself? The affirmation of the artist’s role in society requires that he be recognised as the author of his work – claims the copyrigh – at least as far as having imagined and painted it is concerned. So, from the early Middle Ages when being distinguished for one’s ability and personal gifts was a sin, to the Renaissance, there was a radical change: Albrecht Dürer wrote on his Self-portrait in Fur Trimmed Robe (1500, Alte Pinakothek, Munich) “Thus I, Albrecht Dürer from Nuremburg, painted myself with indelible colours at the age of twenty eight years”. The word “created” was substituted with “painted” in a self-portrait of himself that, according to the conventions of the time, calls Christ to mind. Far from being considered blasphemous – “I don’t see myself as Christ”, but “I aspire to imitate Christ” – it represented for certain his great awareness of the importance of his role as artificer and creator. So then, over the course of the centuries, in the arc of two hundred years, one passes from nothing more than romantic genius to superstar with full recognition – both from the financial and the fame side – of those who make art. A recognition that today, it goes without saying, is ever more synonymous with success.

CHAPTER IV – FACING THE WORLD

- Ai Weiwei, “[Untitled – Hospital selfie]”, 2009, courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, © Ai Weiwei.

- Marina Abramović, “Art Must Be Beautiful”, Artist Must Be Beautiful”, 1975, ZKM | Zentrum fur Kunst und Medientechnologie, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2015.

20th century artists have transfigured traditional methods of representatio – and therefore also of self-portraiture – by using new media and new forms of expression: so now we have performances, selfies, videos, or the use of social media. In her performance video Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful (1975), Marina Abramović films herself with her right hand brushing her hair and her left hand combing it as she repeats “Art must be beautiful, artist must be beautiful”. She stops when she decides to pull out whole chunks of hair from her head and her face becomes a grimace of pain.

Another extreme action, the arrest and wounding of the artist Ai Weiwei by the Chinese state in 2009 led him to post a picture of himself on his Instagram page. Here too the artist displayed his image, the state he was in – with a very immediate gestur – using the extraordinary power of the internet to instigate reflection on the role of the artist today.

The works mentioned above, by Marina Abramović and Ai Weiwei, are being exhibited until 16th October 2016 in Facing the World: Self-portraits Rembrandt to Ai Weiwei, an exhibition organised by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh.

Barbara Bolelli

![Ai Weiwei, "[Untitled - Hospital selfie]", 2009, courtesy of Ai Weiwei Studio, © Ai Weiwei.](http://www.bookmoda.com/site/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/31.jpg)